An essay on parafictional personas.

The aim of this essay is to research the effect of performers constructing alternate versions of themselves as a form of contemporary art - a practise which I will refer to throughout my essay as parafictional personas. It would be unjust to conduct research on the topic of the parafictional without acknowledging Carrie Lambert-Beatty, whom defined the term itself. Beatty deemed in Make-believe: Parafiction and Plausibility that parafiction put simply is when fiction “with various degrees of success, for various durations, and for various purposes”1 are experienced as fact. Thus, parafictional persona is an extension of Beatty’s parafiction by which it is more specific to the construction of a fictional identity. Specifically, it is of interest to me how despite the distinct differences in social, political, historical, and cultural contexts in the works of Wong Kar Wai’s cinematic work In the Mood for Love and Pilvi Takala’s work The Trainee, they both successfully deploy parafictional personas as an avenue to reveal truths with untruths. In the case of Wong’s work, created in the context of Hong Kong’s political unrest and turbulent histories, the characters demonstrate how through the technique of deep role-playing, purposefully created ambiguity can suspend space and time – allowing the characters to explore in a controlled manner, alternate possibilities, real desires, and what-ifs. In the case of Takala’s work, she takes on the fictional persona of a marketing intern to purposefully disrupt the social aesthetics of workplace productivity, exposing the underlying system of a neoliberalist capital society. Ultimately, the action of using parafictional personas is deeply seductive in its ability to help us manoeuvre and reconcile with the complexities and multidimensionality of our reality by creating new understandings and awareness’.

It is necessary to note that there is a lack of published exploration of parafictional personas by artists of ethnicities other than those predominant in the west. This makes apparent a new limitation of the topic parafictional personas itself – “the pragmatics of trust are a question of privilege. Trust is easy won when acting from a privileged position, one which comes with the ability to work as an artist”2. Thus, I was encountered with the difficulty of finding artworks by Asian artists that easily and fittingly sit within the definition of ‘contemporary art’. However, I hope that as an individual who remains connected with my eastern Asian heritage, I can somewhat scratch the surface of parafictional personas and its emotionally resonate powers to a different audience through the Hong Kongnese director Wong Kar Wei’s work In the Mood for Love.

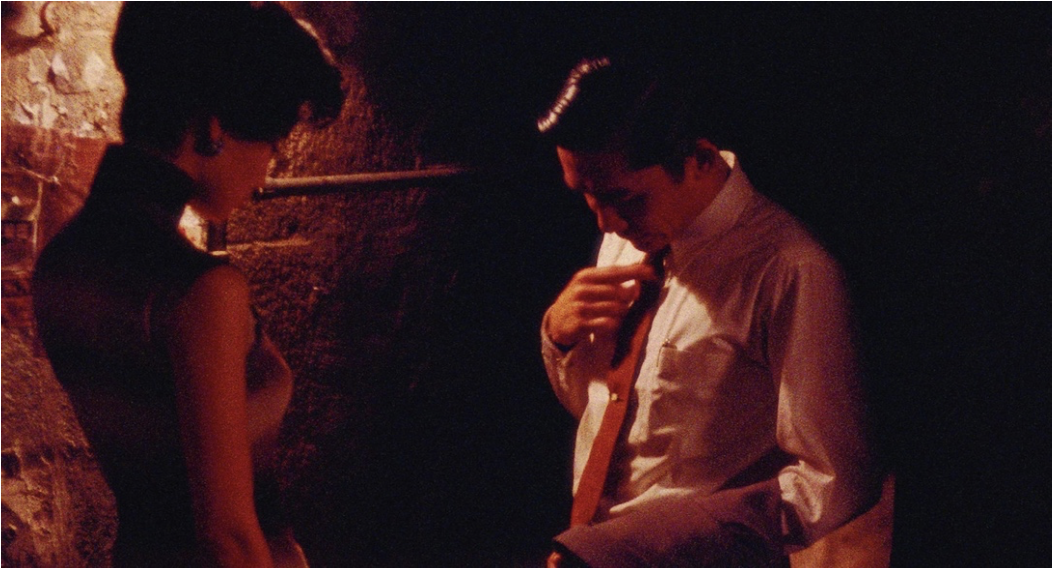

Figure 1: Wong Kar Wai, In the Mood for Love, Video-still, 2000

Even in today’s contemporary era, Hong Kong continues to ride the reverberating shockwaves of its one hundred and fifty years of rule under the British Empire3 and remains caught trying to live the realities of two worlds simultaneously. The handover of Hong Kong in 1997 back to China, left the nation in a whirlwind of gangsterism, ruthless competition, political unrest, turbulent ideals, unstable economies and ungrounded in a coherent national identity or culture. In the contemporary world, Hong Kong continues to live under the ‘one country, two systems’ political structure, an exception to chronological history and occupying a tongue-tied space that aims to reconcile the past with the present. This context is crucial to Wong’s In the Mood for Love as the film ultimately mimics Hong Kong’s dislocation of identity through the use of parafictional personas.

The film revolves around two neighbours who after discovering their individual spouses are cheating on them, engages in an exercise of deep-play by taking on parafictional personas as they attempt to recreate the journey of their cheating partners, hoping to understand why and how the unfaithfulness took over. However, through the character’s repeated use of role- playing, creating parafictional personas, it soon becomes indistinguishable to the audience if the characters are being their fictional selves or real selves ,and the timeline of narrative is no longer evident. For example, as the two neighbours sit across from each other at a restaurant table (Figure 1) engaging in dialogue that would be exchanged on a first date – note that this is also the character’s first date with one another – the camera shifts back and forth between the two. Yet with each shift, the costume of the characters change, creating ambiguity on which of the personas are parafictional and which are real. The repeated change in costumes is often used as a filmic technique to indicate a change in time and place, yet juxtaposed by the scene’s uninterrupted dialogue, the time and place of the film becomes suspended. Accompanied by Wong’s signature use of deep reds, high contrast and melodramatic lighting that only illuminate the silhouettes of characters, slow motion stretching time and dramatically seductive music, the film creates a heightened sense of sublime beauty and highlights the heavenly atmosphere of being ‘in-between’ identities, space, and time (Figure 2). As the audience becomes engrossed in the lyricism of Wong’s presentation of parafictional personas, they are also shown an alternate way of dealing with the complex reality of Hong Kong – to see the evanescent beauty in this transient space of the in-between rather than a desperate and seemingly hopeless reconciliation of the past with the present.

Figure 2: Wong Kar Wai, In the Mood for Love, Video-still, 2000

Figure 3: Wong Kar Wai, In the Mood for Love, Video-still, 2000

Beyond Wong’s use of parafictional personas on a macro level as a way of reconciling with a nation’s identity crisis, it is also used on a micro level to help individuals explore in a controlled manner, their real desires, intense emotions, and what-ifs. For example, as the protagonists hold long heavy gazes (Figure 3), it becomes evident that this freeze frame of movement is actually raging with real attraction and emotional suppression – exceeding the boundaries of simple role-playing or acting and steps into the realm of parafictional personas as each interaction is inherently pregnant with real intentions. The repeated use of such long and intensely held gazes further reinforces the desire to immobilise a fleeing reality4, a careful tip-toe into a constrained space, a way to understand the complexity of their emotions. This credibility of truthiness transported by these parafictional personas becomes most apparent when the female protagonist breaks down in real tears at the loss of this fictitious relationship and the male protagonist must remind her, “It’s only a rehearsal”5. Ultimately, for the moments where the protagonists are supposedly role-playing, they are experiencing it very much as reality. Moreover, to experience the relationship through the medium of parafictional personas rather than their bare selves resolves the dilemma of their desire to act upon their mutual attraction, yet the inability to overlook their morality and scoop to the same level of unfaithfulness as their spouses – as the characters say, “We will never be like them”6. Thus, the protagonists simultaneously occupy both worlds of truths and untruths where their connection is both real and fake – something uniquely achievable through the medium of parafictional personas. Fundamentally, In the Mood for Love showcases a process, not so much of being in a relationship, but more so, of reconciling one’s morality with one’s desire. The characters interaction is not a representation of a romantic relationship, but an attempt to identify with a romantic relationship7 and eventually, we see that this identification fails. The protagonists come to understand that they will never have the courage to undress this protective layer of parafictional personas for they are unable to overcome their moral awareness. Wong’s work paints an aporia of consciousness and provides an avenue for the characters to make informed choices as the use of parafictional personas can provide a most accurate approximation of the real.

Figure 4: Takala Pilvi, The Trainee, Video-still, 2008

In contrast to Wong’s In the Mood for Love, Takala’s parafictional work The Trainee (figure 4) varies significantly in cultural and political contexts. The Trainee which was performed in 2008, intersected with an era of neoliberalist capitalism which pushed for the deregulation of markets such that trade barriers can be lowered and privatised, all in objective to minimise the state’s influence over the economy. However, this resulted in social economic consequences such as the deterioration of income distribution, rise in unemployment, and fostering an environment of intense competition to survive the market.8 Consequently, the 21st century workplace was born into a culture that valued upmost, productivity and the labouring self.

Figure 5: Takala Pilvi, The Trainee, Video-still, 2008

Takala’s works responds to such a context by resisting and subverting the conditions of labour that now shape workers of the contemporary world. The Trainee consisted of Takala playing the parafictional persona Johanna who worked for the global marketing firm Deloitte as a consulting intern. For the duration of one month, Johanna spent time gazing absently into space, lounged around the office space doing some sort of ‘vague thinking’ and continuously rode the escalator lift up and down with no destination (figure 5). Secretly recorded on camera, the employees of Deloitte spent much time exchanging confused glances, forced smiles of bewilderment and disbelief, emails suggesting Johanna having some sort of mental issue and calls to upper management for action against Johanna’s laziness. Thus, when the secretly captured material was exhibited at the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki9, it was made visible to the audience how the absence of performing actions that represent productivity such as a furrowed brow, empty coffee mugs and contemplative sighs, made the presence of Johanna intolerable to the neoliberal capitalist world. Takala’s work utilises the parafictional persona of Johanna to make apparent the politics of being a valuable worker, forcing the very much real, but silent rules of the contemporary workplace to become visible.

Beyond Takala making evident to the audience outside of her work the political imperatives that govern office spaces, The Trainee also confrontingly unmasks this underlying structure to the Deloitte audience within her work, who for the first time, become aware of the rules which dictate their behaviours – the social aesthetics that they so naturally play by without recognising. In this sense, Takala’s work deploys parafictional personas in the form of gay deception10 – a mode where artists purposefully lie to the unknowingly lying audience. For the employees of Deloitte, they have forgotten that the social aesthetics of office culture such as a certain set of behaviours, language, and dress code, is in itself a lie ‘which attempts to faithfully reflect reality, to manage reality, and to transpose it’11. For example, the employees of Deloitte spent a senseless amount of time speculating the reasons for Johanna’s disruptive behaviours however, such speculations were all performed under the disguise of false- productivity. With the use of a “furrowed brow and a concentrated stare”12, to fit in with the social aesthetics of workplaces, the employees’ investment in office gossip and lack of engagement with real work is now acceptable. Then the very core of job performance is not so much measured by actual productivity, but rather by the worker’s ability conduct a self- policing of mimicking productivity. By using a parafictional persona that openly resist such dominant aesthetics destabilises existing structures and provokes the audience within the workplace to reconsider the authenticity of their own personas.

Moreover, The Trainee demonstrates how parafictional personas is not merely a method of art practise, but also the creation of new matter. Such a creation of new matter can present itself in the form of new understandings and awareness of our multi-dimensional reality that live beyond the initial creation of the artwork itself. When Johanna revealed herself as artist Takala, the employees of Deloitte were confronted with the fabrication and social aesthetics of their real workplace. As Takala states, “After I left, the conversation about acceptable working methods continued at the workplace. Whether accepting my behaviour or not, I forced my co-workers to reconsider their expectations of shared rules” 13. The audience within Takala’s work are collided with the new awareness and understanding that the world is fundamentally a system of multiplicities – a layering of the social identity on the individual identity. Therefore, despite the fictionality of Johanna, the effects generated by Johanna were very much real.

A point of interest for exploration is how do the two works of Wong’s In the Mood for Love and Takala’s The Trainee that serve completely different audiences, occupy differing lands of mainstream cinema and fine art, and born out of considerably different social, political and cultural contexts, both successfully deploy parafictional personas as an avenue for truth seeking? This suggests that parafictional personas transcends epistemological accuracy and various contexts that it is made to live in, but rather, its success in is more reliant on plausibility and credibility. As Beatty states:

“In Parafiction, real and/or imagines personages and stories intersect with the world as it is being lived. Post-simulacral, parafictional strategies are orientated less towards the disappearance of the real than towards the pragmatics of trust”.14

In Wong’s work, the strong atmosphere of being in the mood for love created through the craft of filmic techniques allowed both characters to mutually understand the authenticity of their attraction, giving rise to the plausibility of their parafictional personas as the fictive elements are only projections of pre-existing understandings of reality. In the case of Takala’s work, the parafictional persona of Johanna is also very much credible based on the impression that she was able to secure a position at a highly competitive marketing firm. This was further supplemented by her choice of business attire and the support of her presence by upper management. Thus, we see that parafictional personas can transcend genres, contexts, and epistemological accuracy as long as the construction of these personas are credible and plausible.

Through an analysis of Wong’s In the Mood for Love and Takala’s The Trainee, we see that parafictional personas are effective at reconciling us with the complexities of our reality. On a macro level, parafictional personas acts as an avenue for artists to unpack and understand the still unfolding contemporary world. Through a surreally beautiful presentation of parafictional personas, Wong explores an alternate way to deal with the crisis of Hong Kong’s identity - to see the evanescent beauty in this transient space of the in-between rather than a desperate and seemingly hopeless reconciliation of the past with the present. Similarly, Takala’s work aims to make apparent the underlying rigid working structure of a neoliberal capitalist society by utilising the parafictional persona Johanna to make apparent the politics of office spaces. On a micro level, the individual is also deeply affected by the use of parafictional personas. Wong demonstrates how such fictitious personas can suspend space and time, allowing for a controlled environment where individuals can explore their real desires and resolve the paradox of morality and desperation. Likewise, Takala confronts the employees of Deloitte with the fabricated social aesthetic of their workplace and destabilises the authenticity of their own actions. A further comparison of the two works reveals that parafictional personas are not merely a method of art practise, but also the creation of new matter. Moreover, parafictional personas relies little on genres, contexts, and epistemological accuracy but more so the plausibility and believability of their construction. Ultimately, parafictional personas are deeply seductive in its ability to help us navigate the complexities and multidimensionality of our reality by creating new understandings and awareness’.

——————————————————————————

1 Lambert-Beatty Carrie, Make-believe: Parafiction and Plausibility, 2009, p. 54.

2 Smith Rebecca, Parafiction as Matter and Method, 2020, p. 30.

3 The National Archives, Hong Kong and the Opium Wars.

4 Blake Nancy, “We Won’t be like them”: Repetition Compulsion in Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love, The Communication Review, 2003, p. 352.

5 Blake Nancy, p. 350.

6 Teo Stephen, Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love: Like a Ritual in Transfigured Time, 2009, p. 1.

7 Blake Nancy, p. 347.

8 Gatwiri Kathomi, Amboko Julians, Okolla Darius, The implications of Neoliberalism on African economies, health outcomes and wellbeing: a conceptual argument, National Library of Medicine, 2019.

9 Reeves-Evison Theo, Rogues, Rumours and Giants: Some Examples of Deception and Fabulation in Contemporary Art, 2015, p. 200.

10 Reeves-Evison Theo, p. 201.

11 Reeves-Evison Theo, p. 202.

12 Reeves-Evison Theo, p. 200.

13 Reeves-Evison Theo, p. 203.

14 Warren Kate, Double trouble: Parafictional Personas and Contemporary Art, Persona Studies, 2016, p. 59.

References

Blake Nancy, “We Won’t be like them”: Repetition Compulsion in Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love, The Communication Review, 2003, p. 352. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/714858385?casa_token=GXVAOiiI- UYAAAAA:ybetXYaww9Kfic826WFGoTDzhSnV4wKwecWFAM7JZ- Epy8c5mtBbrv0OTXKifQwBJrV5IrTmWL4f

Figure 1: Wong Kar Wai, In the Mood for Love, Video-still, Courtesy of GoldThread, viewed 27 April 2023 https://www.goldthread2.com/culture/wong-kar-wai-mood-love-was-supposed-be-movie- about-food/article/3088012

Figure 2: Wong Kar Wai, In the Mood for Love, Video-still, Courtesy of Normal. , viewed on 27 April 2023 https://normalco.co/2021/01/01/watching-in-the-mood-for-love-on-new-years-eve/

Figure 2: Wong Kar Wai, In the Mood for Love, Video-still, Courtesy of acmi , viewed on 27 April 2023 https://www.acmi.net.au/whats-on/love-neon-cinema-wong-kar-wai/in-the-mood-for-love/

Figure 4: Takala Pilvi, The Trainee, Video-still, 2008, Courtesy of Aalto University, viewed on 17 March 2023, https://www.aalto.fi/en/news/artist-in-residence-pilvi-takala-2018-art-with-your-own-body- by-misbehavin

Figure 5: Takala Pilvi, The Trainee, Video-still, 2008, Courtesy of Pilvi Takala, viewed on 27 April 2023,

https://pilvitakala.com/the-trainee

Gatwiri Kathomi, Amboko Julians, Okolla Darius, The implications of Neoliberalism on African economies, health outcomes and wellbeing: a conceptual argument, National Library of Medicine, 2019 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7223727/#:~:text=Globally%2C%20the%20 rolling%20out%20of,2015

Hong Kong and the Opium Wars, in The National Archives. Accessed on 27 April 2023 https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/hong-kong-and-the-opium- wars/#:~:text=Hong%20Kong%20became%20a%20British,wishes%20of%20the%20Chinese %20government